Balance is defined as the ability for an individual to remain upright and steady. Every year, significant numbers of Americans fall and incur injuries. The following statistics provide insight into why it is critical to appropriately assess and treat balance impairments.

- In 2018, greater than 28% of adults in Michigan older than age 65 reported falling, resulting in more than 35 million falls each year on a national scale.

- Between 20% and 30% of total falls result in some form of non-fatal injury, often broken bones but falls are also the leading cause of traumatic brain injuries.

- Each year about $50 billion is spent on medical costs related to non-fatal fall injuries and greater than $750 million is spent on costs related to fatal falls.

Falls are typically multifactorial, with impairments in muscle strength, gait instability, environmental hazards, acute or chronic immobility, medications, and normal decline/aging of body systems all potentially contributing to an increased fall risk. Our voluntary postural control involves a conscious weight shifting from our center of gravity (COG) to accomplish a goal such as reaching into a cabinet or picking an object off the floor. Age related postural changes include increased sway amplitude, slower movement responses, and a reduced ability to effectively anticipate changes in our environment or body positioning.

Key Components of the Balance System

The three systems that must interact together to keep our heads upright and to facilitate safe movement through space are the visual system (eyes), the vestibular system (inner ear), and somatosensory system (perception of touch). Each of these systems experiences age related changes that impact our brain’s ability to accurately and quickly produce safe motor output (movements) to prevent loss of balance.

Between ~50-65% of our brain is used for visual processing when our eyes are open. When available, visual information frequently overrides that from the vestibular and somatosensory systems and it quickly tells our brains where we are in relation to our world. Examples of having to rely on altered visual information is when we walk across a darkened bedroom at night or navigating through a parking lot during a rain or snow storm.

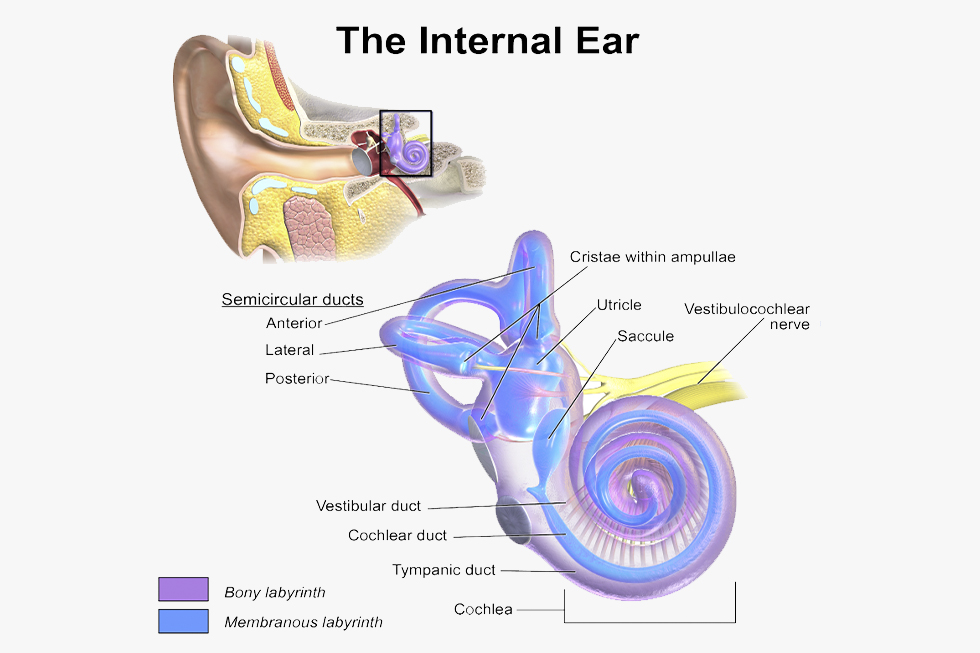

The vestibular system is found within your inner ear and is composed of the otolith organs as well as the semicircular canals. The vestibular system receptors detect and send information to the brain about motion, head position, and spatial orientation. Ultimately, the vestibular system helps us maintain our balance, stabilize our head and body while moving, and maintain our posture. The visual and vestibular systems have to work together to control our vestibular ocular reflex (VOR), which lets our brains know that as we move our bodies through space, the surrounding world is remaining stable. If one or both of these systems is compromised, impaired balance and/or dizziness may result, leading to an increased fall risk.

The somatosensory system is composed of structures throughout the body that help the brain accurately detect touch, temperature, proprioception (body position), and pain. When we are standing and moving about, we have to be able to send somatosensory input to the brain from our feet to produce safe movements and prevent imbalance. People who have peripheral neuropathy in their feet, often secondary to diabetes, have decreased amount and accuracy of this type of information which can lead to increased fall risk.

What should physical therapists look at when assessing balance?

We do not all need the balance of a tight rope walker, but there are critical assessment areas physical therapists should evaluate to determine balance capabilities and fall risk:

- Walking speed

- Ability to safely change directions when walking

- Transitions to standing and onto/off the floor

- Change in sway when required to stand in different positions (feet closer together, standing only on one foot) and/or with eyes closed

- Ability to safely transition onto and off unstable or uneven surfaces

- Stepping over/around obstacles when walking

- Performing head turns to scan the environment when walking

In addition, a key assessment area is a person’s ability to safely dual-task, which could include maintaining a conversation or counting aloud while maintaining a baseline walking speed. Slowed walking speed while dual-tasking with a cognitive skill is indicative of increased fall risk, and will typically increase when an individual experiences either physical or cognitive fatigue.

If you or a loved one are noticing increased challenges maintaining your balance or want to ensure your systems are working properly together, give us a call to schedule a one-on-one evaluation with our Board-Certified Neurologic Clinical Specialist, Kaitlyn Malaski, PT, DPT, NCS.